EXACT AND NATURAL SCIENCES

Vetusodon elikhulu: when the old has something modern

The discovery of a new species of cynodont prompts more questions.

It lived more than 251 million years ago during the Late Permian, in the South African Karoo Basin and, just like any other cynodont, it seemed to have “dog teeth”. It was baptized with the name of Vetusodon elikhulu by CONICET researchers Fernando Abdala and Leandro Gaetano, and their colleagues from South Africa, Roger Smith and Bruce Rubidge, making an official presentation of a new species in the prestigious Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society magazine.

Vetus comes from Latin and means ‘old, ancient’, odontos means ‘tooth’ in Greek, and elikhulu, meaning ‘large’ in Zulu, a widespread language in the African region where the specimens were found. Thus, Vetusodon elikhulu means ‘large old tooth’, in reference to its antique nature and size, both very significant attributes.

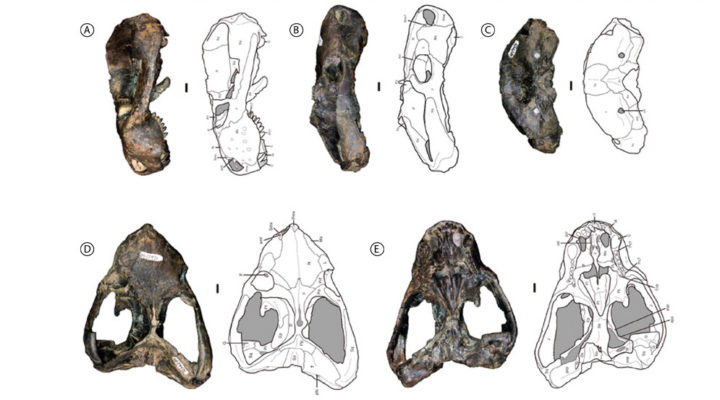

What have they found? Fernando Abdala tells that his scientific studies led him to live in South Africa for 14 years. During field works, he and his local colleagues started finding some materials which did not fit in with other types of craniums already known, but, all of the skulls were incomplete.

Finally, by 2017, the team of paleontologists had gathered four identical specimens, which allowed them to wrap up their work. “Only the snout was preserved from one of the specimens; from another, only the back part. The other two were less damaged: one with the entire jawbone, but we couldn’t see the palate, and the last one had the jaw missing, but the palate was very visible, and it was spectacular!” specifies Leandro Gaetano who joined the group in 2011. Each of the specimens provides different data, such as information about the bones that cover the brain, the palate and the jaw.

From cynodonts to today’s mammals

Cynodonts make up a large and diverse group of four-legged primitive animals that had a curious resemblance to modern mammals. The oldest ones are from the Permian period and were registered in the desert of Karoo, a region that extends throughout two-thirds of South Africa. They were also found in East Africa and Eurasia. How did cynodonts appear?

“Once vertebrates come out of the water, they divide into two groups: one of these groups will result in modern mammals and, the other in birds, dinosaurs, crocodiles, all reptiles…” Gaetano explains. The ones that belong to the mammal group are called synapsids, because they have a hole -or opening- symmetrically located in the temporal bones, and the last lineage to appear is called cynodont”.

“This group also includes us humans. And all these basal or primitive forms allow us to understand how certain specific characteristics have evolved and made modern mammals to be what they are today. For example, in this animal, we can observe that the osseous palate closes from the back part towards the front. This palate presence has to do with the suction capacity to suckle”.

Scientists explain that in this lineage of basal cynodonts many gradual or slow changes can be seen till, finally, by the end of the Triassic –the first period of the dinosaurs era–, the first mammals appear with all the typical characteristics of a modern mammal. “Mammals and dinosaurs coexist since the Mesozoic, from the Late Triassic. There is a moment when dinosaurs start having more preeminence and mammals are reduced. When massive dinosaurs disappear, mammals begin to occupy more space. There’s evidence of both lineages sharing the same habitat as they are historically interconnected. Although they have evolved independently, they influence each other while living together,” clarifies Fernando.

Vetusodon elikhulu, a very peculiar cynodont

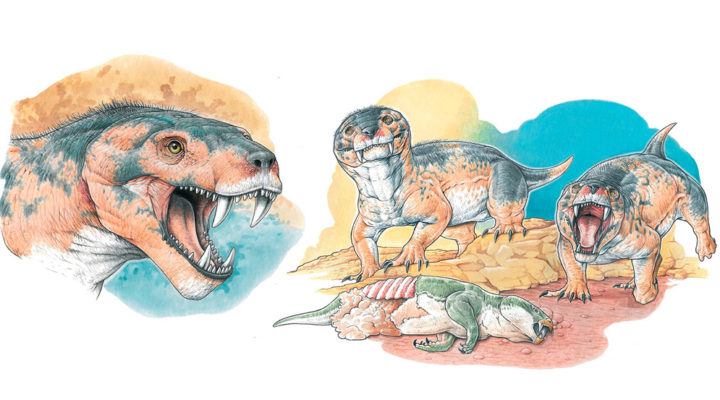

Vetusodon’s first relevant characteristic is its huge size compared to other species of cynodonts that lived at the same time. With its 18-centimeter-long cranium, it is even bigger than species found in the beginning of the Triassic. Scientists estimate that it could have measured up to one meter. In addition, its snout was massive.

The second distinctive feature consists in that, in general, even early cynodonts had very complex molar teeth, that is, their shape was like having many cusps, not like small cones. However, these specimens’ molars have the shape of a cone, which means that, according to their dentition, they were very primitive, similar to more basal synapsid species, previous to cynodonts.

“It’s amazing to find such a huge animal lacking the proper teeth structure to deal with food. Its postcanines were much smaller than its anterior teeth (incisors and canine teeth), which suggests the anterior teeth were probably more important than the posterior teeth. It is the only cynodont whose posterior teeth look like simple small cones,” says Fernando.

“We always thought that, from the beginning of the cynodonts, every change was aimed towards a chewing specialization, as something that improves progressively –Leandro points out– and when the chewing or mastication stage is at its foremost, digression starts towards more specific cases. However, Vetusodon warns us: “No, it was not so progressive!”

This very primitive animal had a very specialized diet: “I imagine it carnivorous and capable of biting off a piece of meat with its strong bite or eating smaller animals with not much chewing,” the scientist illustrates. Moreover, the muscles of mastication and the shape of the jaw also contribute to the theory that Vetusodon used to bite with the anterior teeth with great force, but not with the molars.

Along with the jaw is the ear issue. In the cynodont’s evolution, it is observed that, at the beginning, the dentary bone (which contains the tooth sockets) is relatively small, and it is located in the front part of the jaw. In the back, there are many bones which start reducing in size over time. Thus, from an evolutionary standpoint, posterior bones become smaller, while the dentary bone enlarges. “Back bones grow smaller till they enter into the inner ear becoming the tiny bones of the human’s ears,” Gaetano explains.

“At the evolutionary stage of Vetusodon, the dentary bone is much bigger and the posterior bones much smaller than more advanced fauna that come after it. As a result, we have this very antique primitive animal, but that has a very advanced jaw structure comparable with cynodonts from the Middle and Late Triassic.”

“This shows that the evolution was not so linear or progressive as we thought, although we had a lot of evidence supporting the progressive theory,” scientists admit. Due to the fact that there are many species of cynodonts, they are usually used for evolution models comparison, as they display a very large fossil progression record. However, this taxon breaks the model down.

The last morphological feature brings about more questions: how did the palate form? From front to back, or vice versa? Paleontologists explain that basal or antique cynodonts did not have a secondary palate and, during evolution, the frontal part of the palate is progressively more closed, till the back part closes completely. Nonetheless, Vetusodon’s back part is almost shut and the front part is open.

The cynodont of the change of era

Vetusodon‘s last special peculiarity is not related to a species property, but with its record. It is 251 million years old which means that it belongs to the Permian, the period prior to the rise of dinosaurs. The first dinosaurs are about 230 million years old,” compares Gaetano.

The fact that Vetusodon existed at the end of the Permian in the Paleozoic Era, gives this discovery a unique characteristic: It lived just before the great massive extinction of the Permian-Triassic transition, popularly known as the “Great Dying”. In this severe Earth extinction event, 95% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial fauna died.

The Permian-Triassic transition, marked by this mass extinction, divides the Paleozoic from the Mesozoic Era (the age of dinosaurs). “So, this animal represents the only cynodont discovered at levels that are very close in time with the “Great Dying”. There were other four species of cynodonts in those antique times, but none of them was found so near the extinction,” Fernando affirms.

“Once again, Vetusodon reveals very novel features in spite of its antique nature, and draws our attention by saying: “watch out! This is not yet solved.” These new findings raise more questions than answers,” scientists declare. “We will have to keep on working with colleagues worldwide to put this great puzzle together. It is not possible to work alone in any branches of Paleontology, because in this science there are no geographical or political borders.”

By Jorgelina Martínez Grau

About the study:

Fernando Abdala. Independent researcher. UEL (CONICET-Miguel Lillo Foundation) and University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Leandro C. Gaetano. Associate researcher. IDEAN (CONICET-UBA) and University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.

Roger M. H. Smith. University of the Witwatersrand and South African Museum, South Africa.

Bruce S. Rubidge. University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa.